Well dear readers, I promised you a discourse on Paraguayan history, and you'll probably end up getting more than you paid for.

I started my research at the library of the Mennonite Seminary close by my house. Unfortunately, this soon turned sour because it seemed that, at the seminary at least, nothing had happened in Paraguay since a Mr. Werner Redekopp chronicled a few details back in 1962. Suspecting that perhaps things had happened in this country since that book was published fourty-six years ago (and no, I was not going to read Gilbert Franz's "Reise durch Paraguay" and consider it objective history), I asked around at a couple friends' homes and finally discovered "Historia del Paragauy" published by the esteemed Oceano Group. Really, I know nothing about them, but it seems from their fine cover art that this Spanish firm knows its Paraguayan history. (If there was one thing that I learned after two years as a Goshen College History major, it is that you should always, always judge a book by its cover.) On with the history:

The Guaraní

Surprisingly, (at least to the European adventurers) Paraguay did exist, at least in its geographic form, before the Europeans started showing up at the beginning of the 16th century. There is some debate as to how long humans have lived in South America, but the majority of evidence suggests that people have been leaving things buried in the Paraguayan soil for anywhere between 10,000 and 40,000 years. Three major cultural groups or periods are suggested to have existed prior to 1500 AD, and the latter of these three, the Guaraní, are the people that the Spanish encountered when they started to show up without a dinner invitation.

The Guaraní that inhabited Paraguay (in fact, they were all over central-South America) were a very organized society, with a combination of agriculture, gathering, hunting, and communal living helping to sustain a decent population. That and polygamy. The people had extensive knowledge of the "natural science" of their surroundings, and books chronicling their healing remedies exist in Paraguay to this day. The Guaraní were also polytheistic, holding belief in a number of gods that would control different parts of the natural cycles. (There are actually parallels of Judeo-Christian stories within the Guaraní religious lore, but they are more likely attributable to the influence of Catholic missionaries blending the old, for example, creation stories, with the new Christian version.)

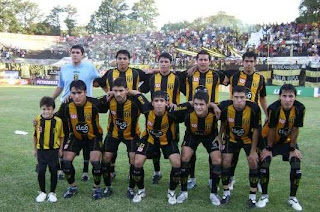

(Modern Guaraní warriors... the club really is named after the people)

But, "without a doubt" say the folks at Oceano Group, the lasting impact of the Guaraní culture on this history of Paraguay is the contribution of the Guaraní language (I would like to insert the "that and polygamy" phrase again here... you will understand when you read the next installment). From my time in Paraguay, I have read a number of different statistics that indicate how many people still speak this ancient tongue, but suffice to say that the lowest estimate that I have so far encountered said that 87.5% of Paraguays are fluent in Guaraní, with other estimates ranging as high as 99%. This explains, dear reader, why I can tell you, "Che aipota tembi'u heta tereí". "I want good food." I learn the basic survival needs first.

The Spanish

Ah, the Spanish. I'm sure many a young Mennonite got lost during sixth grade in daydreams of adventuring with Cortez, Pizarro and the other conquistadores to the New World in search of glory and gold. Of course, to later learn that they basically killed, enslaved, or robbed everyone they met may have thrown something of a moral wrench into the dream, but it was a fine one nonetheless while it lasted.

When speaking of the Spanish explorers who ended up near Paraguay, the story seems to be somewhat repetitve, which is nice when trying to write summaries 500 years or so later. Basically, an explorer (for example, Sebastián Gaboto) gets a mandate from Carlos V, King of Spain, to go and take possesion of the land in what is now South America for the Spanish crown. You know, stick a flag in the ground, build a fort, "civilize" the people you find, and Presto! the land is yours. However, upon arrival, our explorer catches gold fever and tries to set out on some wild expedition into the interior of South America to look for treasure.

Unfortunately, one of these wild goose chases did turn up something under the leadership of Alejo García (credited with "discovering" Paraguay). Mr. García managed to get the foothills of the Andes and pillage an Inca village. He brought back some shiny metal, and then there was no stopping the Gold Rush of the mid-1500s.

However, another common theme of the Spanish adventures was that whatever explorer did manage to make some sort of name for himself inevitably wound up dying at the hands of an angry indigenous mob (Mr. García learned this lesson in 1525). It may have had something to do with the killing, the enslaving, or the robbing. Perhaps two of the three or the whole package. It is hard to say, some folks get angrier easier than others. But it is sufficient to note that no one who came, at least for the first while, ended up hanging around very long.

Finally though, after a couple disasterous preliminary expeditions, the Spanish did manage to make it up the Paraguayan river and set up a fort under the leadership of Juan de Salazar de Espinosa. They christened the new domecile "Nuestra Señora de la Asunción" in 1537.

Look for the second installment of "History of Paraguay": "Polygamy vs. the Cow Head"